Haunted Bauhaus

Category

EDITORIAL

Date

JANUARY , 2022

Location

BILBAO

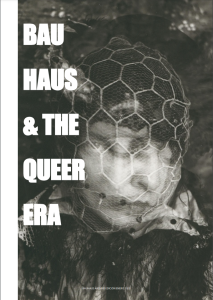

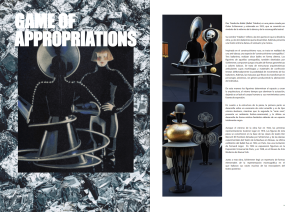

The Bauhaus (1919-1933) is widely regarded as the most influential school of art, architecture, and design of the 20th century, celebrated as the archetypal movement of rational modernism and famous for bringing functional and elegant design to the masses.

In “Haunted Bauhaus,” art historian Elizabeth Otto unveils the Bauhaus history, discovering a movement that is much more diverse and paradoxical than previously assumed. Otto traces the surprising paths of the school’s engagement with occult spirituality, gender fluidity, queer identities, and radical politics. The Bauhaus, she shows us, is haunted by these untold stories, that is so that inspired me to create a little magazine.

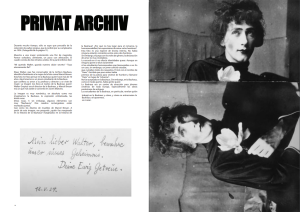

"Mein lieber Walter, bewahre unser süßes Geheimnis. "

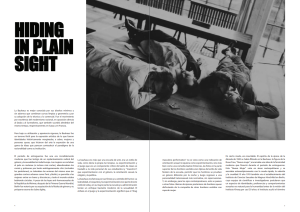

Otto’s book immerses the reader in a diverse artistic and cultural world, previously excluded from narratives about the Bauhaus.

It challenges the prevailing perception of the Bauhaus as a school that only produced rational, male designers and artists, showing that this image is just one facet of its history. According to the book, the school hosted a much richer and varied experimental culture, encouraging and valuing diverse approaches to work and lifestyles.

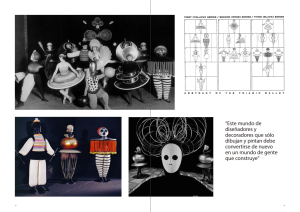

The interwar period was a truly modern era that witnessed a radical transformation in the understanding of gender and sexuality across Europe. Women opted for short hairstyles, abandoned corsets and bustles in favor of androgynous elegance, same-sex unions were tolerated (especially in large urban centers like Paris and Berlin), women gained access to bars and nightclubs, and cocktail culture became widespread. Despite the anti-homosexual laws of the Weimar Republic, post-World War I Berlin became notorious for its acceptance of gender fluidity and its thriving LGBTQ club scene.

The Bauhaus was not just an art education institution but a lifestyle, as expressed by Ise Gropius. The experimentation and play that characterized the classrooms spilled over into the personal lives of the students (and “masters”), who explored issues of gender, sexual orientation, religion, and politics.

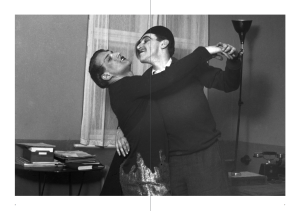

Queer art at the Bauhaus often employed coded images for plausible deniability, as homosexuality was illegal, and even hetero-sexual depictions faced censorship. LGBTQ artists used symbols to convey content to a select audience while denying any gay subtext to authorities. The enigmatic style, exemplified by Heinz Loew’s photo, allowed for multiple interpretations, illustrating the challenges LGBTQ artists faced in expressing same-sex love amid legal restrictions and censorship in German cinema of that era.

This weaving, with rainbow colors and a central triangle, might be mistaken for a gay pride tapestry, but the resemblance is coincidental. The gay pride symbol, an upside-down pink triangle used by the Nazis to identify gay men, was later reclaimed by activists. Bauhausler Max Peiffer Watenphul, known for his paintings, defied norms by entering the weaving studio, typically designated for female students.

Secret Code